Basics of Graph Neural Networks

This guide is a short, intuitive introduction to Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), specifically Message-Passing Neural Networks, aimed for students and researchers looking to learn more about training basic neural networks on graph-structured data. I’ve had many great conversations with labmates and friends who are looking to understand GNNs more deeply, yet find it hard to get to the crux of how these models learn on graphs. In that spirit, I’m collecting some thoughts, perspectives, and pseudocode which helped me understand Graph Neural Networks more deeply when I first started studying them as an undergraduate student.

As a note beforehand, this guide is not meant as a comprehensive review or in-depth tutorial on GNNs; rather, it is meant to build intuition for what is happening under the hood of simple GNNs. Our goal by the end will be to have the ability to point at any operation inside the GNN and explain what it is doing, and what are the shapes and meaning of all the tensors and neural network weights involved. A follow-up blog post will relate the pseudocode shown at the end to real Python and Pytorch Geometric code.

Graphs, all around us!

Data in the world often comes associated with some sort of underlying structure. For example, images come with a 2D grid structure, which allows us to group and analyze pixels within local regions together. We can make assumptions about the data and build these into our neural network architectures in the form of inductive biases, which helps the model learn and generalize on the data. Weight sharing and spatial locality in Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are great examples of this.

Oftentimes, however, the data is structured in a more varied way, with entities connected to one another by relationships in real life. For example, humans are connected to one another in social networks through friendship connections and online interactions, which might be represented as a graph by defining each user as a node connected to other users by edges which represent online connections or interactions through posts. Molecular graphs connect atoms to other atoms through different types of chemical bonds, and a road network might define different cities as nodes which are connected to one another by a web of roads. Any one “node” entity in these graphs may be connected to any number of other entities through edge connections, which means that any neural network we design to learn on this graph-structured data will need to have a very generalized aggregation scheme to effectively integrate information from nodes and their surrounding neighbors. What is the benefit of representing this real-world data as a graph, rather than some other conventional data format? It allows us to flexibly model relationships between any number of entities connected by any number of edges, without having to simplify or project our data into a simpler format.

Furthermore, the entities and relationships we define in our graphs can capture more complexities which we find in real-world data. In social media platforms, for example, think about individual users and companies both being considered users on the platform, who can write posts and be a part of subcommunities. All of these can be defined as separate types of nodes and edges, with different associated feature attributes. We can even have multi-hop relationships (e.g. a friend of a friend), which can make for some fascinating modeling challenges! We’ll leave that for another post, and stick to basic homogeneous graphs for now, where we deal with only one type of entity.

How do we represent graphs?

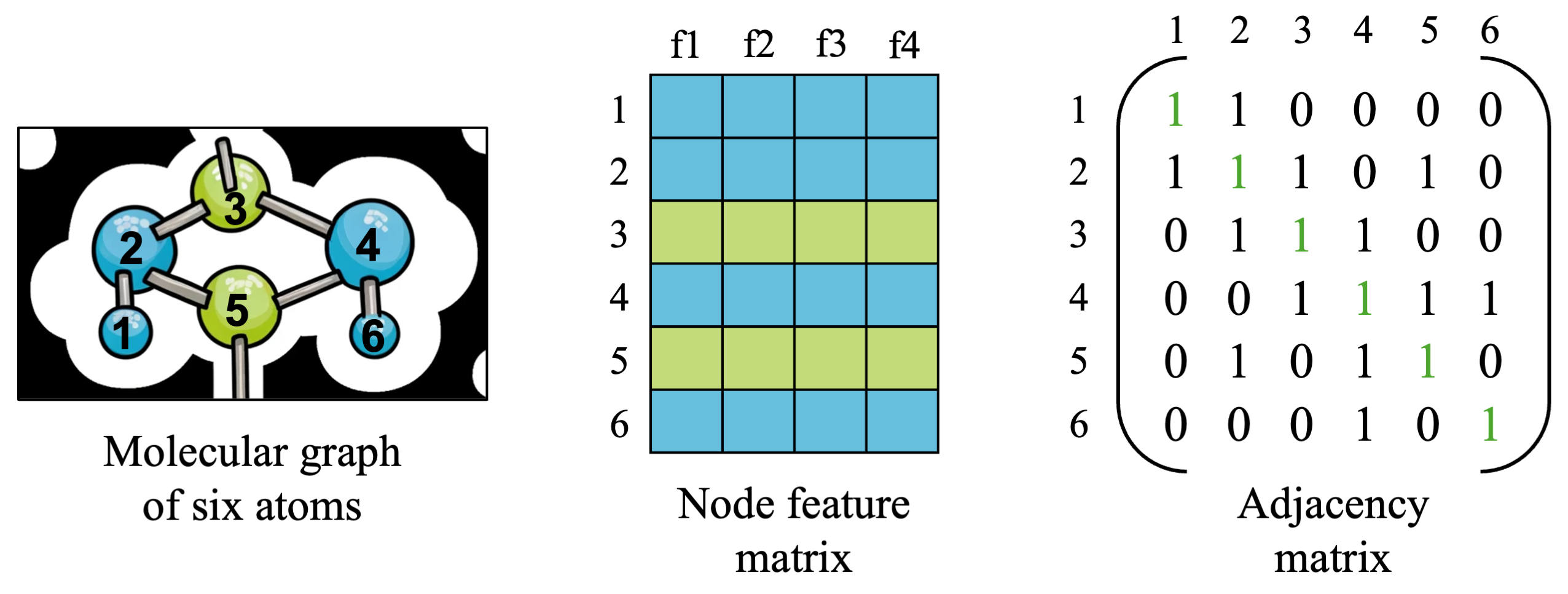

We’ve seen examples of graph-structured data, however we need a principled way of representing the feature attributes and connectivity information of a graph in matrices, so that we can do operations on them and learn from data using neural networks. Let’s define a few matrices which will tell us how we hold the graph data, namely the node feature matrix and the adjacency matrix:

For now, let’s keep looking at a small molecular graph from earlier, made up of six blue and green atoms numbered 1 to 6. We have two matrices which hold all of the information we need to describe a simple graph, so let’s take a closer look and understand what is in each matrix.

Node feature matrix

- The node feature matrix is a matrix which contains all of the features for all nodes in our graph. The shape of this matrix will be [number_of_nodes x number of features], which is [6 x 4] in our small example above, and is usually denoted as \(X\). With \(N=6\) nodes and \(F=4\) features, we have \(X \in R^{N \times F}\). You can imagine that the four features might be attributes of each atom, such as its atomic number, atomic mass, charge, and other relevant attributes.

Adjacency matrix

- The adjacency matrix is a (usually) binary matrix which contains information about what nodes are connected to what other nodes in the graph. This helps us keep track of connections, which we will need once we define a neural network architecture to aggregate information from the surrounding neighbors of each node. Information aggregation in graphs is useful because learning on graphs involves both understanding nodes as well as how they interact with and are similar to their neighboring nodes.

- The shape of the adjacency matrix will be [number_of_nodes x number_of_nodes], which will be [6 x 6] in our small example and is usually denoted as \(A \in R^{N \times N}\). Edges usually have some directionality (a “source” node and “destination” node), so by convention we say that source nodes are the rows and destination nodes are the columns of the matrix, with a 1 indicating an edge between source node \(u\) and destination node \(v\).

- You’ll notice that the diagonal of the adjacency matrix are all 1s, and are highlighted in green. We have a choice in modeling our graph of whether we want to consider a node as connected to itself or not (it may or may not make a difference depending on our data and GNN architecture). For cases where a node’s features or state affects its own state in the future (i.e. an atom’s embedding should reflect the atom’s identity along with other atoms it is connected to), it is generally good to include self-loops. For this simple example, we will include self-connections to connect atoms to themselves.

- You will also notice that the adjacency matrix is symmetric around its diagonal; this means we are working on an undirected graph (atom 1 being connected to atom 2 means 2 is connect to 1 as well). This is not always the case, for example, think about a citation networks: paper A citing paper B does not mean the reverse is true.

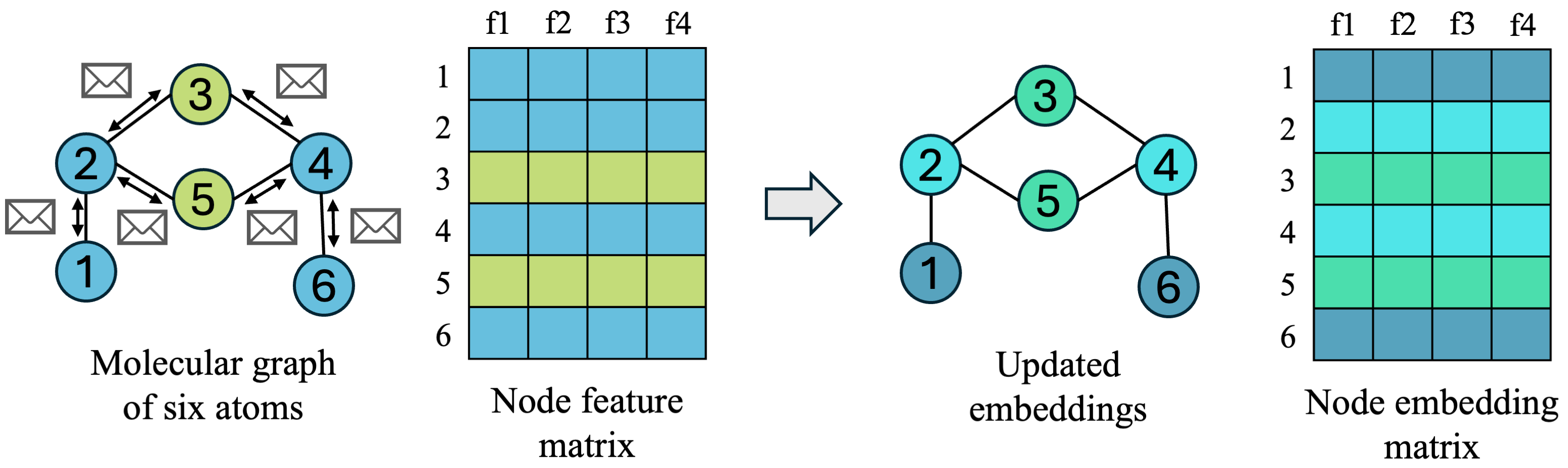

With these two matrices, we have everything we need to numerically describe our graph-structured data. The node feature matrix \(X\) can be seen as initial/input node features, and our goal for learning on graphs will be to learn node embeddings \(H \in R^{N \times D}\), where \(D\) is some hidden dimension which we choose, which meaningfully represent each node for downstream tasks based on both the node’s input features and the neighboring nodes it was connected to. Downstream tasks may include node-level tasks such as classifying what type of atom each node is, edge-level tasks such as classifying what bond type two atoms should have between one another, and graph-level tasks such as predicting whether the molecule as a whole is toxic or not. You can imagine how, depending on the task, it is important for each atom to integrate information from neighboring atoms and have an overall picture of where it is in relation to the whole molecule.

Learning on Graphs: Graph Neural Networks

Now that we’ve seen our data and represented it using node feature and adjacency matrices, let’s get into actually learning on graph-structured data. Because graph data varies in both number of nodes and edge connections between nodes, we need a neural network architecture which can operate on arbitrary node entities with variable number of neighbors while producing meaningful node embeddings for our task. On images, we usually perform information aggregation by taking advantage of spatial locality in images, convolving over groups of pixels to form higher-level abstract features. On graphs, however, we are going to define a graph convolution, which aggregates information from a node and all of its neighbors, and updates that node’s learned embedding in a message-passing step.

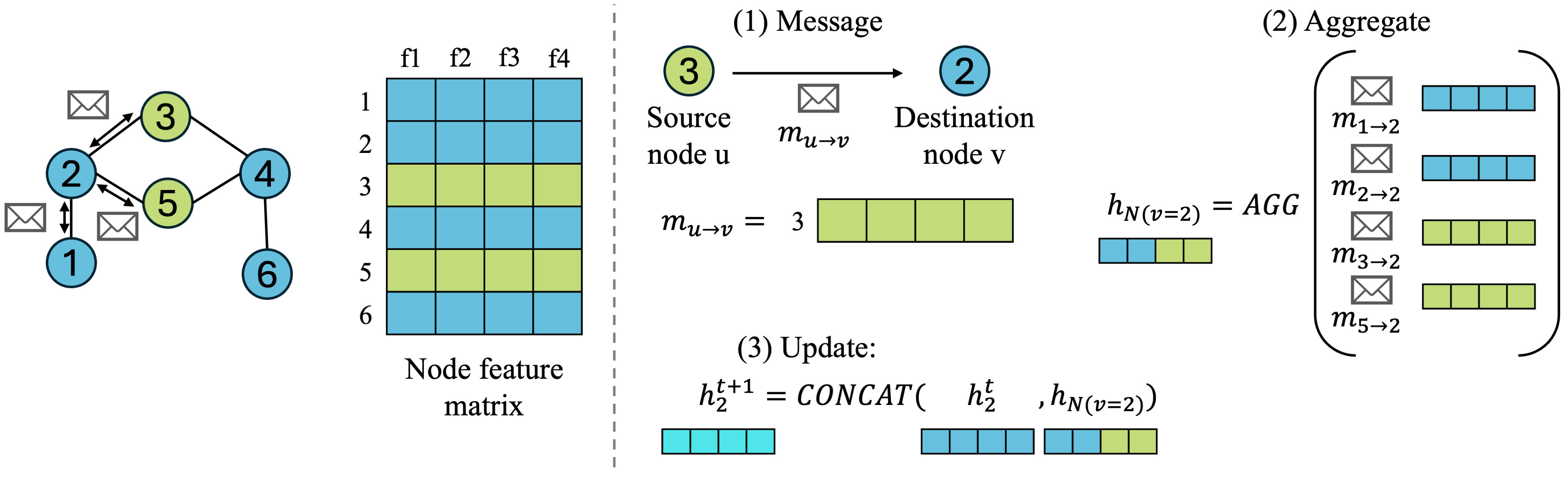

Many GNN architectures have been proposed with varying forms of graph convolutions, and several of the simple, classic GNNs are still used (Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [1], GraphSAGE [2], and Graph Attention Networks [3], to name a few). When learning about GNNs, however, it can be helpful to first start with thinking simply about message-passing neural networks (MPNNs), which is an abstraction of GNN frameworks for learning on graphs proposed in [4]. MPNNs are a general framework where nodes pass messages to one another along edges in the graph in three defined steps:

- Message: every node decides how to send information to neighboring nodes it is connected to by edges

- Aggregate: nodes receive messages from all of their neighbors, who also passed messages, and decides how to combine the information from all of its neighbors

- Update: each node decides how to combine neighborhood information with its own information, and updates its embedding for the next timestep

If we can define these three operations, then we can have all nodes pass each other information in what is considered one message passing step, which disseminates information around the graph a bit. This can be repeated for \(K\) iterations, and the more times we pass information around (larger \(K\)), the more we diffuse information around the graph, which affects the embeddings we get at the end. One way I like to think about this is a group of people spaced 1 step apart from each other, iteratively telling those next to them their name + any other names they have heard from their neighbors. After K rounds of name-telling (information-passing), any one person will have heard the name of all people within K steps of them at least once.

Finally, if we incorporate some learned weights from a neural network into our message-passing operations and define a loss function on the resulting embeddings for some downstream task (e.g. node classification), then we have all of the ingredients we need for learning on graph-structured data.

Let’s zoom in a bit on each step for one destination node \(v\), define some notation, and visualize how the node feature matrix and adjacency matrix are going into each operation:

- Message: source node \(u\) will pass message \(m_{uv}\) to destination node \(v\), which is node 2 in our small example.

- What exactly is the message? It depends on the GNN architecture! For simplicity, we will go with the easiest message node \(u\) can give to node \(v\), which is just passing its node feature \(h_u\) vector to \(v\). More complex GNNs might do some learned operations to come up with a better message.

- Aggregate: we can choose some aggregation function to combine information from neighboring nodes, such as SUM or MEAN, which works across any number of neighboring nodes. This gives us a combined neighborhood node embedding denoted as \(h_{N(v)}\), where \(N(v)\) denotes the neighborhood of destination node \(v\), meaning all nodes connected to node \(v\).

- \[h_{N(v)}^{k+1} = AGGREGATE({h_u^k, \forall u \in N(v)})\]

- Note: a special note about the aggregate operation is that we usually need to choose a permutation-invariant function to aggregate neighboring node messages. This because neighboring nodes don’t have an ordering with respect to the destination node, so our aggregate function needs to give the same output no matter the ordering of the inputs.

- Update: we can concatenate the neighborhood embedding \(h_{N(v)}^{k+1}\) with the embedding of the node itself, \(h_v^k\), and parameterize it with some learned weights \(W\) and a nonlinearity \(\sigma\) to form our final update step:

- \[h_v^{k+1} = \sigma(W \cdot CONCAT(h_v^k, h_{N(v)}^{k+1}))\]

And now we’ve done it! We’ve made it through one message passing step, and if we repeat this for all destination nodes v, then we have our updated node embeddings for the next timestep \(k+1\).

A general algorithm for message-passing

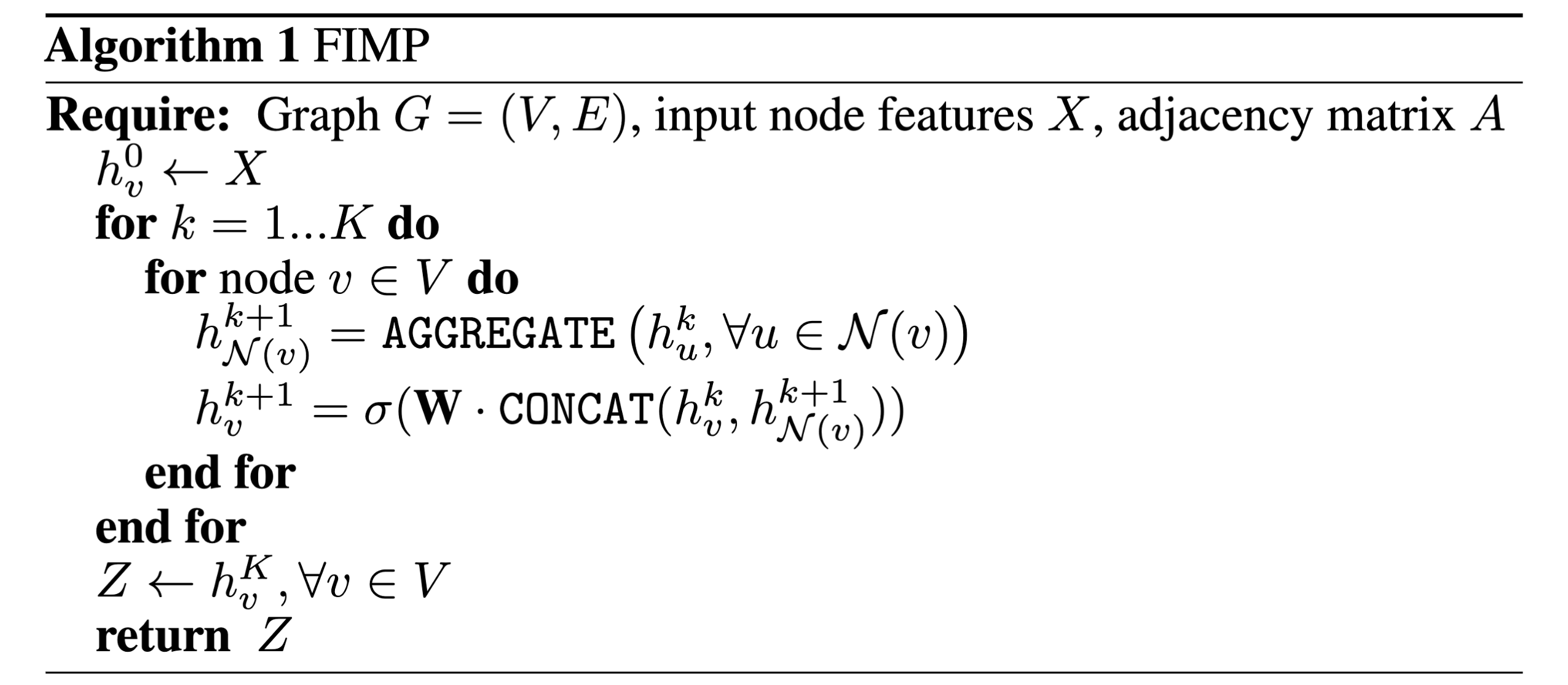

The GraphSAGE paper [2] introduces a pseudocode algorithm for message passing which I quite like, and will put below for those thinking about the overall algorithm. This is actually the first algorithm I dissected as an undergraduate student to understand each operation and relate it to code implementations (which I will do in another blog post!).

It is quite a powerful algorithm when you think about it: in one code block, containing 10 lines, we can define a sequence of operations that encompasses how all MPNNs operate on arbitrary graph-structured data, and can become arbitrarily complex depending on how you define each of the three core operations: message, aggregate, and update.

Connecting things together

The nice thing about thinking through the message-passing framework is that we can recover many classical GNN architectures depending on the choice of message, aggregate, and update operations. Here are a few examples I like to think of (simplifying a bit for the sake of explanation):

- If we choose our permutation-invariant aggregator to be a simple averaging, and include self-connections in our adjacency matrix, we can recover the original GCN architecture [1]. The GCN formulation defines this as a matrix multiplication: \(\tilde{A}XW\), which does the aggregation through matrix multiplication with a normalized adjacency matrix \(\tilde{A}\).

- In the message step, what if we consider how much the source node is important to the destination node, and assign a score for that edge? We could weigh the edges with these scores if we normalize them correctly, for example by making all incoming edge scores sum up to 1. Then, our aggregation is a weighted aggregation, which is more informative than assuming all neighboring nodes have the same importance. This is the main idea behind GATs [3].

Final note: thank you for reading through to the end of this blog post! I appreciate your attention, and hope these ideas are useful to you in your work or studies as much as it was useful for me when I began studying GNNs. As this is my first blog post, I’d greatly appreciate any comments/tips/suggestions! The best place to reach me is at my email: syed [dot] rizvi [at] yale [dot] edu.

References

- Kipf, Thomas N., and Max Welling. “Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907 (2016).

- Hamilton, Will, Zhitao Ying, and Jure Leskovec. “Inductive representation learning on large graphs.” Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

- Veličković, Petar, et al. “Graph attention networks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.10903 (2017).

- Gilmer, Justin, et al. “Neural message passing for quantum chemistry.” International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2017.